(Mouseover any identifier to decode)

So, in the doors I walked, on 8 April, 1968, just barely 22 years old, ready to give instructions to airplanes; clear them up, down, across, and through. Frankly, ever since I had gotten the phone call, I had been thinking about that IFR trip from HWO to SRQ; thinking about how the controller sounded, his authority, confidence, etc. I thought about that chapter in Kershner; I could picture the radar scope and I knew that there was a position next to it that took care of the flight progress strips on which was recorded all of the aircraft flight information. Later I learned that the D controller, the one with the strips, provided non-radar separation, and handled much of the communication with adjacent facilities. But for then, I was excited at the prospect and looked forward to sitting down at the radar that first day and getting started.

It was, therefore, quite a shock to meet my new neighbor, W.A. Marshall, who had been at Jacksonville since 1965. He had just recently completed D school, and was training on the boards to be a D controller (the person who took care of the strips). I was not pleased to learn that it had taken three years for him to get to that point. But that wasn’t the worst of it. The process at the time was to go to D school, complete D training on the boards, and then go back to working Flight Data and the A side. One then had to bid on openings for D positions, work there for a number of years once selected, and then eventually get trained on the radar (R) positions. Then one had to go back to the D side and wait for an opening on a radar position upon which to bid. I wanted to talk to airplanes; I had never quite understood the meaning of crestfallen before then, but a dull awareness began to creep in.

Not all was negative, however. The school was challenging, and there were some really nice people there. Our instructors were Gene Griffin and Dave Bray, both of whom were only a little ahead of W.A. in the training process. They were sharp, affable, and stern taskmasters. The other students (I recall there being about 25) were a wide cross section; one was a retired B-52 pilot, another was a psychology graduate, and yet another was a former military controller with eight years experience, some of it in Berlin Center (but long after the Airlift). His name is Len Williams, and he and I are the only ones from that class that made a whole career.

In the first week we were presented alist of 330location identifiers to memorize. We were given a list of the airways in the Jacksonville area, and we were introduced to the art of drawing maps. In order to pass Flight Data School, we had to draw a map of Jacksonville Center. We were given a blank sheet of paper, approximately 18x30, and were required to draw all of the airways, high and low, with names and mileages; all of the VORs; and all of the NDBs. Naturally, in order to draw a map good enough to pass, one had to draw some practice maps; lots of practice maps. It was intense, it was hard work, but all in all, it wasn’t bad work. We got plenty of breaks and plenty of practice.

But, if one had any hope of getting through the school, one had to study off duty. We would study by ourselves, we would study in small groups, we would study in large groups. A couple of guys were married, and their wives would study with us. They would call out identifiers to us, and we would respond; consistently mixing up GSB (Seymour-Johnson AFB) with GSO (Greensboro, North Carolina), and Wilmington, North Carolina (ILM) with Wilmington, Delaware (ILN), with Wilmington, Ohio (ILG). They would name an airway, and we would give the fix postings for it. They would name an airline and we would give the identifier for it. They would name an airplane and we would say prop or jet, single or multi-engine, and name the nominal speed.

We socialized, too; after all, hard work, dull boys, and Jack, you know. Some of us in the study groups, and others who had formed their own, often took the weekend as an opportunity to escape the work and explore the area. It wasn’t much, really. Hilliard was a town of approximately 1,000 people, and only a small percentage, maybe 50 people, worked at the center. Most were pulp wooders, involved in growing and harvesting the lumber grown in the area for the paper mills. There were only two paved streets in Hilliard and one traffic light. There was a grocery store, a convenience store, a hardware store, a post office, a couple of gas stations, and three bars. Learning the area, therefore, involved locating the nearest restaurants, and other bars. Callahan was 10 miles in one direction, and Boulogne, a village that had lost its charter from the state as a result of traffic citation abuses to the tourists on U.S.1 and 301, was 7 miles in the other. There were motels and taverns scattered along the way on that route, and we tried them all.

Along about the second or third week (a long dim detail, now) we were issued headsets—the venerable Bell Model 52. It was a huge deal for me. It was like affirming that I was on my way to being an air traffic controller. It was so impressive that when my parents and I met for lunch in Titusville a week or so later, I brought it along to show them. I’m not sure I ever actually used it. We used handsets in Flight Data and on the A-Side and with the possible exception of stick time on a position, really had no need for a headset until D School.

Despite all of those years of seeing movies of telephone operators (and Ernestine on Laugh In) using those Model 52s, they were horribly uncomfortable. Oddly, even until the day I retired, there were still a couple of old timers around who preferred them. By the time I got to the D-Side I had graduated to this Plantronics MS50, “the headset that went to the moon,” instead. The MS50 was light weight, but with the headband, it clamped firmly in place and there was nothing you could do to de-stabilize it.

Sadly, when I got to Chicago, they only had StarSets, which I detested, but I was stuck with one for the remaining 24 years. The StarSet hung from your ear, and moving the mouthpiece, the spring in the earpiece tube, the cord catching on your collar, all tended to dislodge it. Very disconcerting for the engrossed controller. They had an eyeglass clip so when I started wearing glasses, I used that, but it only improved it by 50%.

Sometimes we made forays into Jacksonville. There were some interesting bars there, and there was the Gator Bowl. Jacksonville, as one would expect in a large city, had major stores and some shopping centers; malls hadn’t quite been invented, yet. And then there were the beaches, and the navy bases, and the golf courses. We didn’t lack for entertainment.

Some of my high school classmates were then in the last semester of their senior year at the University of Florida in Gainesville, which was only 80 miles away, so I spent a couple of weekends reacquainting myself with the world of academia. I blew the top off a piston in my car on my way down there one weekend, which wound up costing me two weeks without transport, more money than my beginning salary allowed, and an exposure to overland bus travel that I don’t care to revisit.

One morning, as I was preparing to go to work, I heard on the radio that Bobby Kennedy had been assassinated. It seemed unremarkable then, what with all the Vietnam activity (Tet was still ongoing), and King having been assassinated just two months before. 1968 was a rocky year.

We would frequently get settled down at our desks after a break and Gene or Dave would walk in and say, “I have a Wilmington estimate.” That was the sort of thing you would hear on the phone when working flight data, so we all grabbed our pencils and strips and started copying the flight plan they gave us. “Eastern 241, a ’727 slant Alpha, 480 knots, estimated ILM 1545, Flight Level 310, off of JFK, J79 MIA.” He would give his initials, signifying the completion of the flight plan, we prepared the strips, they would grade them, and then, “I have an Atlanta estimate.” It was there we learned the joy of the one-stripper. High altitude flights on J43, for example, only required one strip; a TLH strip; and to go from a copied flight plan to a finished strip only involved a few pencil strokes. It followed, then, that we didn’t get too many one-strippers to do in school; most of the time, and to the point of the school, we got flight plans that averaged three or four strips.

What we were learning to do was process flight plans. Each flight that was handled by the center had a series of flight progress strips prepared for it that indicated: callsign, type of aircraft, true airspeed, time, altitude, and route of flight, in addition to some other coordination markings. The flight data positions that we would be working would copy flight plans from other centers, from flight service stations (FSS), and from military operations (BASOPS). Once we copied a flight plan, we had to prepare a strip for each sector whose airspace the flight would traverse. By prepare, I mean write. 95% of the strips used were handwritten.

The rest were prepared by a machine called a Cardatype (I’m sure that must have been an IBM trademark name, but let them sue me!), which was used to prepare flight plans that generated a lot of strips. And by “was used”, I mean by a Cardatype operator. We in Flight Data School were exposed to it, learned to operate it, but rarely employed it on a regular basis. That was the job of the Cardatype operator, the lowest rung on the ladder in the control room. I finally found an image. This example is even configured for printing our flight progress strips, as you can see both to the left of the image and behind the machine on the right.

The rest were prepared by a machine called a Cardatype (I’m sure that must have been an IBM trademark name, but let them sue me!), which was used to prepare flight plans that generated a lot of strips. And by “was used”, I mean by a Cardatype operator. We in Flight Data School were exposed to it, learned to operate it, but rarely employed it on a regular basis. That was the job of the Cardatype operator, the lowest rung on the ladder in the control room. I finally found an image. This example is even configured for printing our flight progress strips, as you can see both to the left of the image and behind the machine on the right.

Some flights had only a few strips prepared. Our favorites, of course, were the one strippers previously described, which a good flight data person could complete while copying it and other flight plans. Others, such as J45-J77 from ATL over JAX down to MIA only needed two. The bears were V157, for example, which needed seven strips (FLO, VAN, ALD, abeam SAV, AMG, AYS, TAY, and GNV. Sometimes we would get an estimate on a J79 flight (CHS, abeam SAV, abeam JAX) only to have the aircraft change altitude from FL240 to FL220. Then CRE, abeam SSI, and DAB strips would have to be prepared for the low sectors. A flight from, say DCA, to JAX required CHS, abeam SAV, JAX, for the high altitude sectors, and abeam SSI, and JAX for the low sectors.

To get an idea of how many strips we prepared, consider our traffic count, which was measured by counting departures, multiplying by two and then adding overflights. The theory was that every aircraft that departed had to land somewhere, so rather than counting arrivals, it was easier just to double the departure count. The cases where a flight departed in one center and landed in another were figured to even out. In any event, Jacksonville passed the 1,000,000 operations per year mark, then a benchmark for busy facilities, in 1970. That averages to more than 2,700 operations per day. Considering that weekends were much less busy than weekdays, it is fair to assume 2,800+ operations per day in those years. If one assumes an average of 4 strips per flight, that amounts to more than 10,000 strips prepared per day; all hand written. It is no wonder that, to this day, I hate to write anything by hand. Thank goodness for computers and the typing class I took in high school!

In order to grasp how necessary the computer was to us, I remember working the day we first had a 2,000 count. We were very busy. So, somewhere between 1968 and 1970, our traffic had increased significantly to average 2,800 operations per day. The record for one day in Chicago, set in 1995, is over 10,000!

For us to get to the point where Gene or Dave could say, “I have a Wilmington estimate,” we had to know the location identifiers, the airways, the airline identifiers, and the equipment types. In order to prepare the strips, we had to know which fixes to post strips for, we had to be able to add times quickly, and we had to have some knowledge of aircraft types in case some bozo in another facility didn’t know that Electras only did 320 but that tri-jets did 500. We also had to learn some strip marking protocol; for example marking down arrows on the last strip for an aircraft landing at a particular airport, or marking an overflight symbol on the last strip of a flight transiting the Jacksonville area. We had to learn which part of the strip got the altitude and how to process a flight upon which we had gotten erroneous information.

We also learned the fundamentals of a technique called “short stripping,” which entailed only partial route information on intermediate strips (the ones other than the first and last)—the first strip had the full route, because that’s what you copied the flight plan on—the last strip because the remaining full route had to be passed on to the adjacent facility. I say fundamentals, because you had to be a pretty good Flight Data person to be able to effectively do it, and at this point, we were far from pretty good.

One day after school, I picked up my mail and went back to the motel. In the middle was one from the Selective Service System, Local 150 (I was still registered in Hollywood—I seem to recall that in those days they didn’t reassign you to another jurisdiction when you moved). That was my local draft board, from which there were periodic announcements or requests for information. This one, however, began with, “Greeting.” It was not good news.

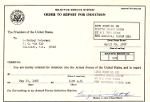

By the way, over the years, I have heard of people receiving draft notices, and they always talked about “Greetings,” but there is no “s”…trust me. This is my actual notice. Note the “Greeting.” Note the happy phrase at the top: “ORDER TO REPORT FOR INDUCTION”

By the way, over the years, I have heard of people receiving draft notices, and they always talked about “Greetings,” but there is no “s”…trust me. This is my actual notice. Note the “Greeting.” Note the happy phrase at the top: “ORDER TO REPORT FOR INDUCTION”

Recall that in the Introduction I talked of taking the AFEES physical in January, well before I got the call from the FAA. At that physical, the doctor had reviewed my medical history, which consisted of some significant damage to my ankle, and which he considered rendered me unfit for service. He didn’t stamp me 4F, but he said I wouldn’t be called at the current state of military need. He apparently didn’t convey that clearly to the local board, and they decided they wanted me. In all fairness, Tet had begun between the time I had taken that physical and the time I was hired, but an inability to trudge through swamps was a shortcoming that applied equally to those circumstances, in my opinion.

I tried to convince the secretary of the local board (the only person one could contact) that I had already been through the process. I had my doctor forward (again) the X-rays and the diagnosis to the board. I even got the FAA to write a letter extolling the worth of my continued employ in government service, in particular my contribution to the national defense. That wasn’t a trivial argument—military traffic is possibly 20% of total IFR operations, depending on the facility—it was much lower in Chicago, but in Jacksonville we had at least thirteen military facilities contributing lots of traffic—for one, Moody AFB in Valdosta, the demand even necessitated a sector dedicated solely to their operations.

However, the draft board bureaucrat instructed me to just go ahead and report, and that during the examination part of the process, my infirmity could be confirmed, and I needn’t be concerned. That was quite a cavalier solution, given that I had to pack up all of my possessions, return to Hollywood, and report to Coral Gables, frankly not knowing whether I would be eating dinner that evening at home or in Fort Jackson, South Carolina. But they were intractable, and that is exactly what I did. I was relieved and delighted that my ankle was still bad, and I returned to Jacksonville eager to complete my training. A new draft card stamped 1-Y (“registrant qualified for military service only in time of war or national emergency”) arrived a few weeks later. Considering the packing and travel time, and the reporting day and the day after, I was gone a week, but fortunately, I was well along in the training regimen, and I didn’t really miss anything (the recent discovery of my actual draft notice sheds some modern light on the timetable, and I now suspect I missed the 7th week of an 8 week class—given how things turned out, I must have been in the pro forma phase of the class, as I passed the tests). I was forever bitter at the draft board for that but I don’t think I held a unique sentiment.

Once we had completed flight data school, we went on to something called AOS. I never have known what AOS stood for (I’ve been informed by a fan—a real dinosaur— that it stands for “Airways Operations Specialist”—an ancient designation for air traffic controller—thanks, Gene!), but it taught us things ancillary to the job of a controller, such as aviation weather, navigation, and some of the instruments that a pilot used, but cruelly, that position was projected to be a long way off for us headed for flight data or assistant’s job. With my background, most of it was a snap for me, but believe it or not, there are lots of controllers with no flying experience whatsoever, and I understood the difficulties some of them had in learning what a VOR actually did and what its presentation looked like in the cockpit. AOS was an uneventful four weeks of which I don’t recall much. For an instrument rated pilot with fresh ink on his license, it was a cake walk—I can’t even remember any notable things from it—and by June we were downstairs training in Flight data.

A half dozen of the people that had been in flight data school with us had actually completed AOS first, and some new people in AOS with us went to flight data school after AOS, so although I feel a kinship with all the people that were in both my classes, only those with whom I had both classes together truly started in the FAA at the same time. I think we were all anxious to get downstairs and begin work in the control room, even if it didn’t mean saddling up to a radar scope right away.

Last updated: 03 June 2016